Converting metadata to linked open data.

The Peniarth Manuscripts form one of the most important collections held by the National Library of Wales. Its 560 manuscripts date from the 11th Century onward and contain some of the most important and iconic Welsh literary works in existence, including stories from the Mabinogion, the Book of Taliesin and the earliest copies of the ancient Laws books of Wales. In 2010 the collection was included in the UNESCO UK Memory of the World Register, further underlining its importance as a national treasure.

The collection has of course been catalogued and digitisation of the entire collection is currently underway. So now seemed like a good time to explore the potential of linked data in order to better understand and explore the makeup of the collection.

At the National Library of Wales we have now converted collection Metadata to Wikidata for a number of collections including paintings and printed material. This has lead to an enrichment of data and easy access to tools for querying and visualizing the collections. Creating Wikidata for each of the Peniarth manuscripts would result in similar advantages, but first the existing metadata would have to be cleaned and refined before being mapped to entities within Wikidata. Some mappings were easy, for example metadata tags for parchment and paper were easily matched to the relevant Wikidata entities. Dates and measurements simply needed formatting in a particular way in order to add them to Wikidata, and the QuickStatements (QS) upload tool contains detailed instructions on how to do this.

Much of the data already existed in set data fields making mappings fairly straight forward. However the metadata for many manuscripts also included a text based description of the item, which in many cases included additional information such as the names of scribes and people whose works are represented within the manuscript (authors). Extracting this data was more difficult. By filtering searches for specific sentence structures and/or certain keywords it was possible to semi automate the extraction of this data, but it also required manual checking to avoid mistakes. Once the names, works, subjects and genres were extracted they then had to be matched to Wikidata items. If these items did not yet have a Wikidata item, they were created whenever possible using data from other sources.

The ontology for describing manuscripts on Wikidata is still being tweaked, so in order to properly separate and describe both the scribe/copyist of a work and the authors of works included in a manuscript it was necessary to create a new property on Wikidata, which can now be used to describe the scribe, calligrapher or copyist of a manuscript work.

Once the data was prepared in a spreadsheet it was uploaded to Wikidata in stages using the Quickstatements tool. We also uploaded sample images of the 100 or so manuscripts which have already been digitised to Wikimedia Commons. Since the implementation of structured data on Commons any upload which links to the relevant item on Wikidata it now pulls in much of the relevant descriptive data automatically, meaning there is a lot less work involved in preparing a batch upload of images than in days gone by. Since the National Library uses IIIF technology to display its digital assets, we also included persistent id’s to our image viewer and links to IIIF manifests in our Wikidata upload.

Once the data is uploaded it can immediately be queried and explored using the Wikidata SPARQL Query Service. This tool has a suit of visualisation options, but there are a number of other useful visualisation tools which can be used in conjunction with a sparql query without the need for any coding knowledge, such as the Wikidata Visualisation suit and RAWGraphs.

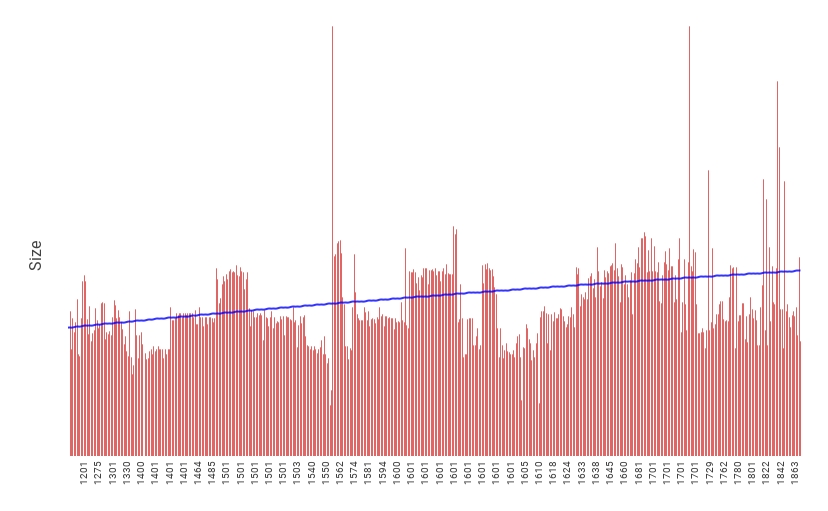

In many cases it is technically possible to retrieve the same data from standard Metadata as you can from the linked data – it’s just that we don’t have the tools to easily do so. For example we could easily list manuscripts from smallest to largest, or oldest to youngest, or perhaps explore the relationship between the size of a manuscript and the date it was created.

Interestingly, this query clearly shows a trend of increasing size in the manuscripts over time and it also seems to point to a trend towards producing manuscripts of similar sizes at different periods in time.

We can also easily analyze data about the language of the works in the collection. It’s worth remembering that many works contain texts in more than one language, but we know that 43% of items contain Welsh language text whilst 33% contain English and 19% contain Latin.

Whilst this is definitely useful, the extra information extracted from text descriptions in the metadata begins to enrich and add further value to the data, allowing us to perform new queries on the data. For example we can attempt to break down the collection by genre and main subject for the first time. This of course is only as accurate as the original data, and in some cases the variety of content within a single manuscript makes it impossible to apply an overarching content type, but in terms of research and discoverability, the data certainly provides new insight. For example, we can identify all manuscripts which contain correspondence, and then see who the main subject of those correspondence are, and because Wikidata is linked data we could then access biographical data about those people.

Many of the manuscripts in the Peniarth collection include copies or partial copies of other notable works, in fact some of the manuscripts are copies of other manuscripts in the same collection. Using Wikidatas ‘Exemplar of’ property it was possible to connect the manuscripts to data items for the works they contained. Again, I suspect the original metadata does not identify all the works included in the manuscripts so the results of any query will not be exhaustive but they will represent all of the current data in our catalogue.

See the full visualization on Wikimedia Commons. See the Sparql Query

We can see from the visualisation the no fewer than 22 manuscripts contain text from the codification of Welsh Law by Hywel Dda, 21 manuscripts are copies of other manuscripts in the collection and 12 are exemplars of various printed books.

Using the newly created Scribe property on Wikidata we have been able to link data for each manuscript to the data items for every scribe mentioned in the metadata. Three scribes stand out as the most prolific, with their hand writing appearing in dozens of Manuscripts. Two of the three, Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt and W.W.E Wynne of Peniarth once owned much of the collection and did much to annotate and copy the texts. The third, John Jones, was a well known collector and scribe, and is credited with copying many texts which might otherwise have been lost forever. By exploring which scribes contributed to which manuscripts we can identify connection between otherwise unconnected individuals.

See the Sparql Query

Finally, it’s important to underline the fact that Wikidata doesn’t just allow us to explore individual collections in new ways, it acts as a hub, joining collections together in an ever expanding web of cultural heritage data. We have added a lot of data for people in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography for example, and a simple query now allows us to identify all of those who contributed to the Peniarth collection.

In the same way, we can link to collections in other institutions, many of whom are also beginning to add their collections to Wikidata. Oxford University is one such institution and this means that manuscripts of Welsh interest at Jesus College like the Book of the Anchorite of Llanddewi Brefi and the Red Book of Hergest are now connected through linked data to the copies of those manuscripts in the Peniarth Collection.

Run the live query on the Wikidata Query Service

As more and more collections are added to this huge linked open network we will increasingly be able to reconcile, explore and make sense of our combined cultural heritage, which for hundreds of years has existed in closed silos. By applying new technology and Open licensing, cultural institutions can now breath new life into old data, and reach a wider audience than ever before.

Jason Evans

A WordPress Commenter September 22, 2023

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.